The circular economy is nothing new. Although it is a concept that is much talked about today, it was an everyday practice in our grandparents’ time, especially in rural areas, where the old maxim of the father of chemistry, Lavoisier, was naturally and obviously applied: “In nature, nothing is created, nothing is lost, everything is transformed”.

These were hard times and almost nothing was wasted. What little was left over from meals or cooking was fed to animals or put on the compost heap to fertilise the soil. Plastic was still a novelty, more common in urban areas, and grocery shops bought food in bulk, in packets of butcher’s paper, which was also used to wrap fish, ham or sausage. Beverages were sold in glass bottles, which were religiously kept in order to return them to their place of origin and recover the value of the packaging, and bread was packed in cloth bags that each customer carried with them. Shoes were repaired at the cobbler’s, clothes were mended at the dressmaker’s and reused by different members of the family.

In this way, people lived in greater harmony with the cycles of nature, with some shortages but without excesses. Without excessive consumption and without excessive waste, including food waste.

From ancient to modern times

Today, global food waste is estimated to be at an absurd level, equivalent to around a third of what is produced, and to make matters worse, much of this waste ends up in landfills or dumps, taking up space and going unused.

Ironically, while we have succeeded in creating artificial intelligence and private space travel, we have yet to solve the problem of food waste and world hunger.

With much of the world’s population living in urban centres, where farmland, gardens and backyards have given way to roads and buildings, food waste ends its life in landfills or dumps. This interrupts the cycle of organic matter and deprives the soil of much-needed nutrients. On the other hand, this waste contributes to the problem of climate change through the emission of greenhouse gases.

Bio-waste is part of our daily lives. It is present every time we prepare food for a meal and when we throw away leftovers. On average, they make up almost 37% of our “normal” waste bins. As they decompose, they produce unpleasant odours; they mix with other materials (e.g., packaging, paper and cardboard, textiles) that many people still put in their normal waste, contaminating it, and making it difficult to separate at the sorting lines; and above all, they represent a loss of an important resource – nutrients – that could be used for national agricultural and forestry soils.

What has been written on the subject?

In an attempt to reverse this situation, the European Commission has developed policy guidelines and advocated various strategies to promote the circular economy, the separation of bio-waste and the practice of composting, both at household and industrial level.

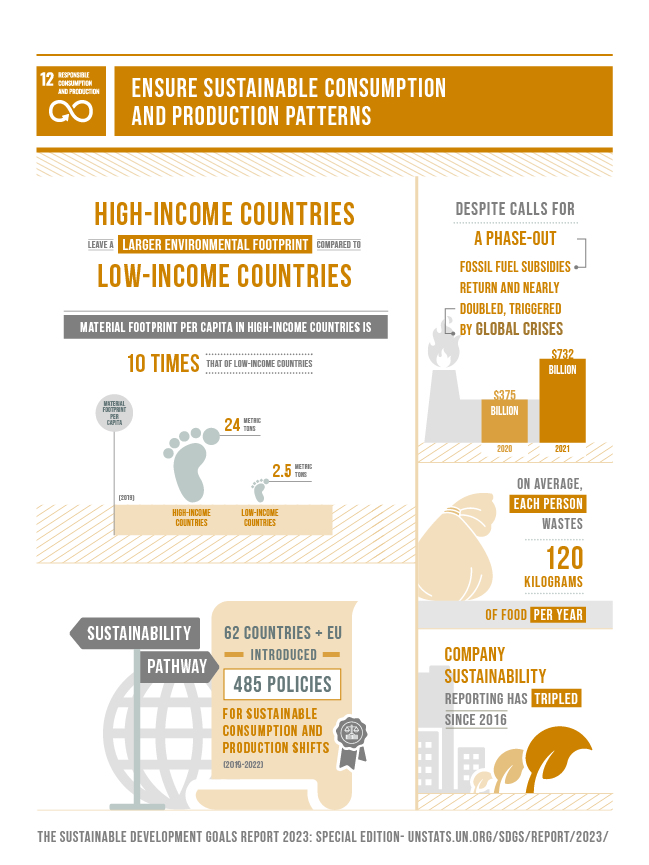

On the other hand, SDG 12 (Sustainable Consumption and Production) of the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals proposes a series of actions relevant to this Plan, among which the following stand out:

-Halve food waste per capita globally.

-Significantly reduce waste generation through prevention, reduction, reuse, and recycling.

In December 2019, the European Commission presented “the European Green Deal (EGD)”, with the aim of transforming the European Union (EU) into a modern, resource-efficient and competitive economy, thus key to implementing the 2030 Agenda and the SDGs”.

One of the main foundations of the European Green Deal is the new Circular Economy Action Plan (CEAP), published in March 2020, a roadmap for environmentally responsible and socially just growth, which proposes measures to be implemented throughout the life cycle of products, with the aim of preparing the economy for a green future, strengthening competitiveness (while protecting the environment) and granting new rights to consumers, according to the Strategic Plan for Urban Waste (PERSU 2030).

PERSU 2030 also states that “building on the work done since 2015, when the first CEAP was published, the new CEAP focuses on the design and production phases in a circular economy, with the aim of ensuring that resources are kept in the production and consumption system for as long as possible, namely through measures in sectors with a high circularity potential (electronics, packaging, plastics, food, textiles)”. Another of the main actions of the CEAP is the “Meadow to Plate” strategy, which aims to create a fair, healthy, and environmentally friendly food system, in particular by reducing food losses and promoting short production and consumption circuits, or by favouring the regeneration of nutrients and organic matter in the soil”.

What can we do?

By moving towards bio-waste collection and recovery, we reduce our reliance on landfill and incineration, decarbonise society, optimise the efficiency of packaging and cardboard recycling, reduce the use of synthetic fertilisers, and promote improvements in soil quality. While home composting is more common in rural areas, industrial composting through anaerobic digestion is already a reality in urban areas in some waste management centres, allowing the production of large quantities of compost and also biogas for use in the national electricity grid.

The challenge for policy makers and local authorities in particular is to develop realistic and feasible strategies and methods to promote the circular economy of organic matter in society. These include door-to-door collection, the distribution of home composters, the installation of community composters, and the organisation of training and awareness-raising activities in schools and among residents. To make this a reality, it is important to involve citizens and make them aware of the importance of bio-waste recovery and its benefits for the environment, the economy, and the population in general.

“Awareness-raising and environmental education play a fundamental role, as the subsequent good results are based on and largely depend on a change in behaviour leading to an active and involved environmental citizenship. This is in addition to the articulation with the vision, objectives, goals, targets, and measures of other reference plans in this sector,” says PERSU 2030.