Any technological innovation has always aroused mixed feelings, with enthusiasm for the benefits of new possibilities and fear of the consequences they may bring. Artificial intelligence (AI), which is being used in many different sectors, is certainly no exception. It has now entered the field of communications, publishing, and journalism with a vengeance.

This sector, which has already undergone major changes in recent years with the transition from print to web, the spread of the Internet, the impact of social networks, information overload and the consequent tendency to avoid news, is once again faced with new tools and the need to innovate and adapt to new technological developments.

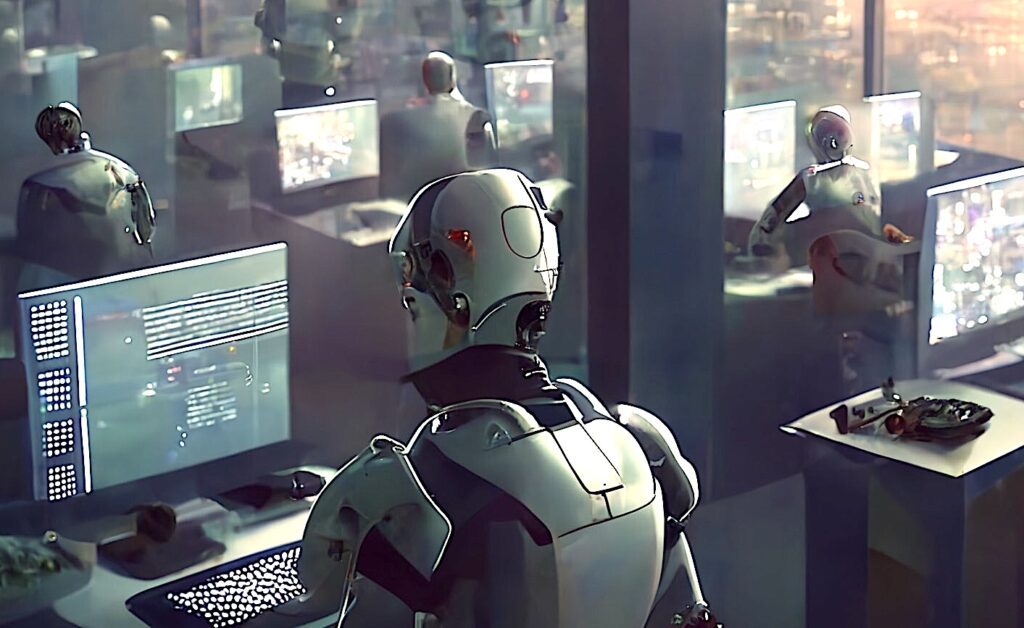

The integration of GAI (generative artificial intelligence) technologies into journalism has understandably raised concerns that AI could undermine jobs and erode the credibility of the sector, which has already declined significantly in recent years.

On the other hand, ‘journalistic robots’ could only take over the most repetitive and monotonous tasks, without completely replacing human editors, who will have to constantly check what this technology produces.

In fact, machine-generated texts are often full of errors, biases, and banal concepts. Another risk is the difficulty of tracing the source of information provided by a generative AI, which compromises the ability to verify the accuracy of the information. Even to the point of finding bibliographical references, as Vincenzo Tiani denounced during the last International Journalism Festival in Perugia, to articles or essays that were never written.

THE CURRENT SITUATION

Artificial intelligence tools already in use in newsrooms allow news gathering processes to be optimised through automated monitoring of events and trends (in social networks, news agencies or press releases) and through automated extraction of information from large volumes of data (big data).

It also improves the productivity of journalists through automated tools such as assisted editing, transcription of audio or video, rewriting or summarising text and adapting it to the type of channel and specific target audience.

Publishing sales also benefit from systematic analysis of user preferences, profiling based on reader behaviour and habits, also with a view to subscriptions.

WORLDWIDE

In many parts of the world, Generative Artificial Intelligence is not just the preserve of large publishers, but is also making its way into smaller newsrooms, increasing coverage of automatable content such as sports scores, weather forecasts and personalisation of the local experience (Argentina’s Diario Huarpe is one example).

In some US newspapers, it is an algorithm that decides when to charge users for articles (Wall Street Journal) and tries to predict readers’ reactions (New York Times), while in South Korea it goes as far as cloning popular TV presenters using DeepBrain AI.

In the UK, traditional newspapers are analysing user behaviour to develop fully data-driven content strategies (The Times), but new automated local news services are also emerging that can use a data-driven approach to analyse data, discover stories, generate copy and publish thousands of these pre-edited articles every week (Reporters And Data And Robots).

IN ITALY

In Italy, large-scale experiments have begun with semi-automated newsrooms, the implementation of intelligent CMS (content management systems) and the proposal of personalised experiences for readers.

From an operational point of view, AI is being used to speed up editorial workflows, automate operations such as transcription and translation, generate data-driven content without replacing journalists and, above all, personalise the user experience to encourage subscriptions by analysing online behaviour.

At the moment, machines are not capable of writing quality articles on their own. The valuable contribution of journalists remains irreplaceable, but they may become subservient to the machine. They may soon have to incorporate the control and monitoring skills of AI systems into their repertoire.

The digitization process reached a turning point in 2019, when online advertising revenues overtook TV for the first time. Although the share of online advertising revenues currently stands at around 49%, representing almost half of total advertising revenues, it is important to note that the hegemony in this sector is firmly in the hands of Google and Meta, which hold 80% of online advertising revenues in Italy.

At the same time, traditional media are in decline, as evidenced by a significant drop in the total revenues of the Italian media sector in 2020, with sharp declines in television, radio, newspapers, and magazines.

Despite this picture, an interesting fact emerges from the same report: for the first time, a “digital native” news site such as Fanpage was the most visited, along with Tgcom24 (21%). Fanpage, which started as a Facebook page, is now one of the most popular newspapers in Italy, thanks to its variety of content, ranging from entertainment to research. Fanpage even outperforms large chains such as ANSA (which remains the most trusted brand at 73%) and other established newspapers.

Other positive online results were achieved by digital newspapers such as HuffPost (9%), Il Post.it (7%) and Open (4%), which seem to have succeeded in targeting niche audiences that are often overlooked by traditional newspapers. The fact that Il Post has reached 50,000 subscribers shows how the audience is truly becoming a community.

This shift is also evident in the emergence of new companies such as Chora Media, which offer an experience that actively engages the audience and makes journalistic stories more tangible and engaging.

REGULATION FOR THE FUTURE

It is clear that with the potential benefits of this new technology come real risks, and it is certainly no coincidence that the European Union is trying to rush the deadlines for the adoption of the AI Act, the EU regulation that will regulate the sector at the end of the legislature and try to minimise its risks.

There are also risks in journalistic applications of artificial intelligence. Indeed, the ethical and deontological aspect of these tools has yet to be defined, taking into account issues such as content authorship, copyright and the protection of personal data.

On the other hand, among the risks already present in the use of AI, in addition to possible mass surveillance through facial recognition or “Minority Report”-style preventive policing, the lack of regulation would leave room for a possible increase in the spread of social prejudices, stereotypes and more sophisticated disinformation, including propaganda.