A report examines two decades of hospital admissions in Spain, from 2000 to 2021, and provides some worrying data. General admissions decreased by 23% while mental health admissions have doubled.

The data corroborate what many sectors have been denouncing for years and, especially, after the confinement of the pandemic. Adolescents have more mental health problems, and they are not decreasing, but increasing.

The researchers behind the article ‘Hospital admissions in adolescents with mental disorders in Spain over the last two decades: a mental health crisis?’ have reached several clear conclusions after reviewing the figures for hospital admissions and discharges among young people aged 11 to 18. The first of these is that there is indeed a mental health crisis among adolescents.

Admissions for mental disorders have not stopped growing steadily since the beginning of the millennium and although they have increased more in 2021, the last year of the study data, the researchers assure that the mental health crisis experienced in Spain, as in other developed countries, is not caused by the pandemic.

In these two decades, while hospital admissions in this age group for conditions other than those derived from mental health have decreased, they have gone the other way.

Over time changes

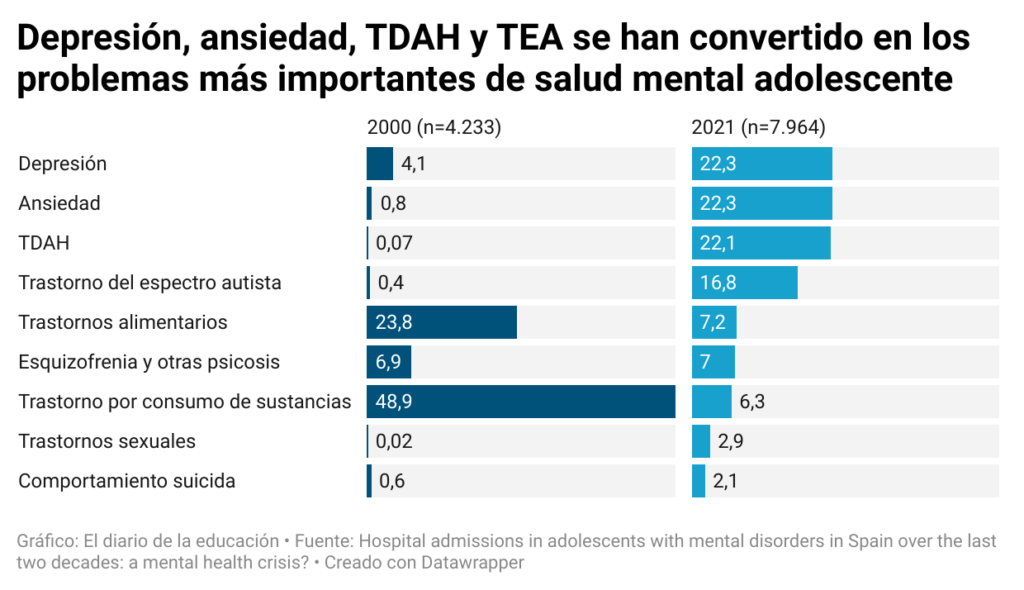

The researchers found that some of the main causes of hospital admissions have changed since the pandemic.

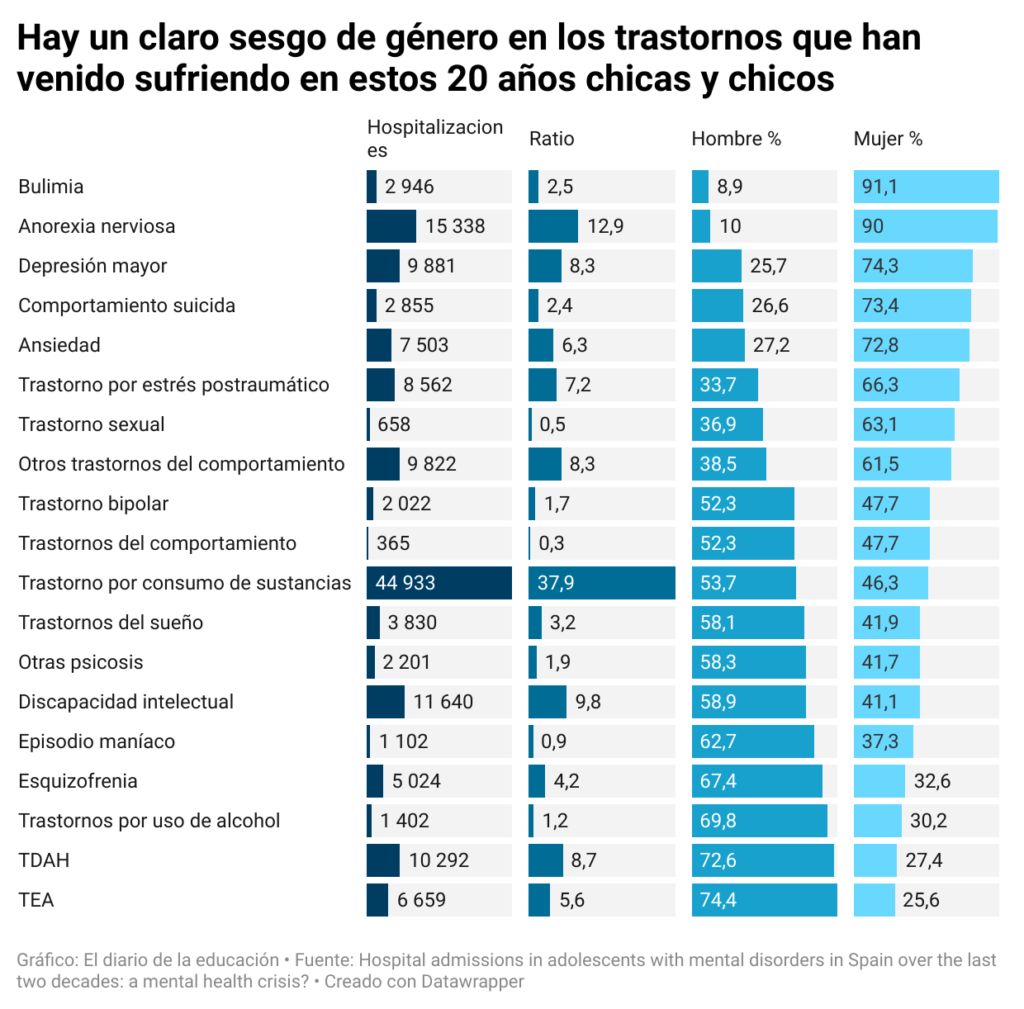

The most common cause of hospital admissions for boys is substance abuse, while for girls it is anorexia nervosa. But in recent years, there have been some changes.

In the case of girls, their ailments are related to what are known as internalising disorders, i.e., depression and anxiety, mainly. In addition, there are eating disorders and suicidal behaviours. Moreover, they are in the majority, accounting for 55% of total admissions, and the average age of admissions has dropped from 17 to 15 years old.

Behind them are children whose disorders are rather externalising, i.e., related to substance abuse, ADHD, ASD, schizophrenia and other psychoses.

According to the experience of Hilario Blasco-Fontecilla, child and adolescent psychiatrist and director of the research, this situation is quite common, with boys suffering more neurodevelopmental disorders in the first 10 to 12 years of age and girls and adolescents experiencing more internalising problems after menarche.

Possible causes

In any case, Blasco-Fontecilla insists that Spain, like many other Western countries, is experiencing a mental health crisis among its adolescents. A crisis that is not only caused by the pandemic and confinement, even though hospital admissions, according to his data, rose by 51% in 2021 compared to 2020.

From their point of view, the role of screens and social networks, which is not always positive, as well as fathers and mothers who do not have quality time with their daughters and sons, who do not seem to know how to exercise parentally, are frightened and sometimes so overwhelmed that they delegate part of their work of accompaniment to the health systems.

“Social networks have been very pernicious in general,” she says. From his point of view, they have a very addictive component and the companies behind them “do it knowingly because, in the end, it’s a business.”

But, beyond the screens or social networks, “what it is really teaching us is that parents seem to have given up their parental functions,” says this psychologist. From his point of view, and beyond the study, a social change has been seen in recent decades, not only in Spain, according to which fathers and mothers spend long working days away from home and when they get home, they have little time and energy to devote to their children. For him, certain values of society have been transformed while changing concepts related to the family. For him, there are great emotional deficiencies that drag boys and girls by a way of life that has left them relatively isolated.

Notes for a solution

Solving the current situation does not seem to be an easy task. Blasco-Fontecilla points out, in fact, that even if the administrations were to invest significant amounts of money now in certain solutions, results would not be seen for some time.

In this sense, the paper they have just published, points out as one of its intentions to show the data so that some measures can be taken from educational policies to improve prevention actions that can be carried out in schools.

“Mental health has to enter schools,” says the researcher, who points out that although some steps have been taken with the creation of the figure of the welfare coordinator, this has to be developed.

Another of the actions that should be taken in schools is to introduce different professional profiles in the classroom, beyond the teaching staff. Personnel such as occupational therapists, speech therapists, psychologists… For this expert, it is necessary to strengthen the links between education and health, in addition to improving the training of teachers to detect possible cases of mental health problems.

And beyond what may or may not be done in educational centres, he believes that the healthcare system has been failing for years in preventive healthcare as well. “One of the problems we have in Spain is that we have a lot of care pressure and very few professionals”.

Blasco-Fontecilla believes that, in addition to investing in professionals, “we must be realistic and encourage innovation. I have no shame in admitting that we must move towards models in which artificial intelligence and virtual assistants are introduced to facilitate, not replace, because it is not a question of substituting, that we professionals become more efficient”.