For young people, digitalisation represents a major trap; sometimes having more likes, playing online games and other online interactions discourages them from participating in face-to-face social and sporting activities.

It is not true that only older people feel lonely. There are multiple indicators that show emotional distress and lack of social support. The latest wave of the Enquesta de Salut de Catalunya (2023) shows that 22.1% of citizens have some emotional distress and that 25% have no one or only one or two people with whom to share their problems.

However, loneliness is not only a lack of social relationships, but above all dissatisfaction with existing relationships or the absence of these, warns Dr Juan Carlos Durán, from the Hospital San Juan Grande in Jerez de la Frontera, in SOM Salut Mental, an initiative of 14 organisations under the umbrella of Sant Joan de Déu, to provide information and raise awareness about mental health. In other words, although isolation can be a determining factor, it is not synonymous with loneliness. The image of elderly people alone at home is thus removed. Loneliness affects them, yes, but also young people who spend the day in front of their mobile phones.

“We are detecting an increase in loneliness beyond the elderly,” explains Juanjo Ortega, director of the social work of Sant Joan de Déu, which carried out an awareness campaign as part of the week against unwanted loneliness at the beginning of October, “25% of children and young people say that at times they feel lonely and, in many cases, have no one to confide in”. According to Ortega, the loneliness of the elderly is marked by the death of family and friends and by physical limitations, a situation that is aggravated in rural environments, and therefore the response must be to achieve an active life: “You have to overcome laziness and get out of the house”.

For young people, however, digitalisation represents a major trap. “Now it is easier to pretend to have a social life from home”, warns Ortega, who points out that having more likes, playing online games and other interactions through the net discourages people from participating in social and sporting activities in person, “life from the sofa avoids conflicts because it is enough to simply unfollow, but when you have problems, the networks no longer work”. Now, in the face of bullying, fatphobia, racism… it is easier to isolate oneself in technology, breaking down the networks of mutual help.

All this goes hand in hand with an increasingly individualistic world. Now almost everything can be done from home: getting information, shopping, playing games, watching films… But this means meeting up less with friends, not talking to the people in charge of the local shops – which are increasingly being swallowed up by online sales and large supermarkets -, not getting to know neighbours, not getting involved in local organisations… Even work can now be done from home, reducing the number of places to meet with work colleagues.

The director of the social work of Sant Joan de Déu warns that this tendency towards isolation means the breakdown of community networks, a situation which, in the case of families with second homes, is even worse, as they often spend weekends away from the municipality where they go about their daily lives, so that their children are less able to relate to their daily environment: “It is a structural problem, so we need to strengthen social life with small businesses, school team sports, reading clubs…, any attractive space which, without trying to do so, is socialising”.

Youth

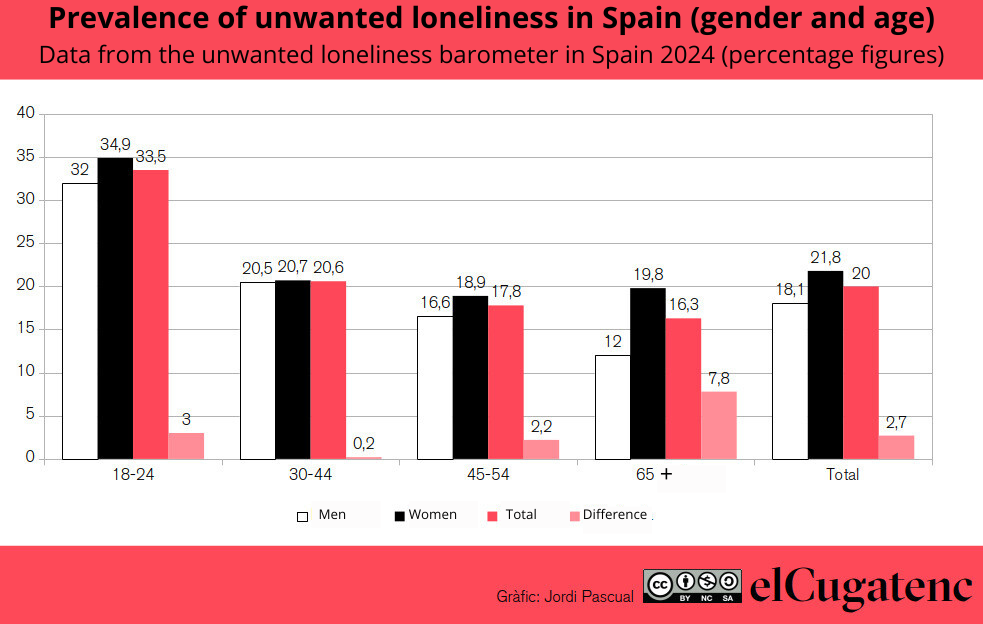

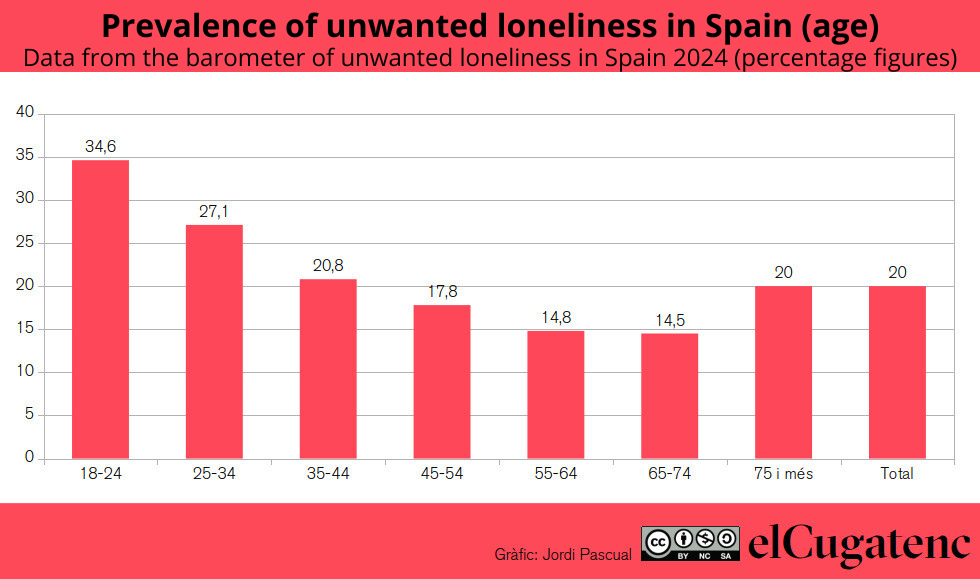

A study by the State Observatory on Unwanted Loneliness shows that 25.5% of young people aged between 16 and 29 are in a situation of loneliness, 5.5 points above the average for the population as a whole. In fact, this represents more loneliness than among older people, since the lowest prevalence of loneliness (14.5%) is recorded among those aged between 65 and 74, and it is just after this that there is an upturn (up to 20%, values comparable to the 35-44 age group and exactly the average calculated by the Observatory).

Laura Gallego, social worker and referent of Escolta Jove, a programme of emotional accompaniment promoted by the Provincial Council and that comes to Sant Cugat through the OhFicina Jove!, explains that it is very important to take care of mental health, especially in adolescence, because it is when people build our identity. The service has just started operating this September and, so far, they have not detected any cases of loneliness, but they have detected an abuse of screens that can pave the way to this problem. In fact, the OhFicina Jove! is also home to the 1 Segon advice service on drugs and screens, which depends on a plan drawn up by the City Council.

The aim of these services, explains Gallego, is to be able to refer young people where necessary to ensure good care. For this reason, they go to secondary schools to explain the existence of the services and also propose workshops in schools through the Educational Dynamization Programme, an opportunity to talk about the feeling of belonging to a group, bullying, empathy and exclusion, among other topics. The collaboration is completed with the mental health round table, which brings together organisations and services that carry out activities related to mental health. In this way, Escolta Jove can maintain direct contact with professionals from educational and health centres, as well as with specialised services for young people, such as the Centre de Salut Mental Infantil i Juvenil (CSMIJ).

Older people

Beyond the alarm represented by the data on loneliness among young people, the elderly continue to be a group at risk, as the loss of mobility is added to the death of friends and relatives and the lack of visits from children and grandchildren. “80% of the people who come to the Llar d’Avis are widowed women”, warns Joan Cortadellas, president of the Llar d’Avis de la Parròquia de Sant Cugat, which, together with the other six homes for the elderly in the city, carries out essential work so that the elderly can meet and carry out all kinds of activities. The Llar d’Avis is attended by 750 people, 600 of whom are members. For Cortadellas, who is also vice-president of the Consell de la Gent Gran, it is essential to ensure that the neighbourhood centres are active and, if possible, to open more in order to avoid long journeys that people with reduced mobility cannot make: “Coming here forces them to leave the house and get ready, while staying at home means dying a little every day”. However, some of these homes need volunteers and revitalisation to ensure that they play their proper role.

Care for the elderly is also of concern to the administrations, which, beyond the home care services that offer support for a few hours a day, promote programmes to deal with unwanted loneliness. This is the case of the Provincial Council’s Nexes programme, which in 2023 intervened in 300 cases with the aim of reaching a thousand beneficiaries. This programme is aimed at people over 65 years of age who have already been detected by the social services through telecare or SAD, or through the municipal census, with the aim of guaranteeing support from the organisations and the neighbourhood to improve their wellbeing.

Migration, precariousness and isolation

Another determining factor in loneliness is migration, as new arrivals often do not have a support network in the host society, and so it takes time for them to build one. However, Gabriela Poblet, PhD in Social and Cultural Anthropology, lecturer at the UAB and director of Europa Sense Murs, explains that the lack of a social network does not automatically lead to a situation of loneliness, although it is true that reception links are reduced with the gradual disappearance of call centres and other spaces where migrants could meet and share experiences. It should also be borne in mind, the professor warns, that the profile of migration has changed, with an increase in migration due to violence, which is generally associated with greater mistrust.

“Many workers work 24 hours a day all week long”, warns the expert in reference to those who work as live-in care workers for elderly or dependent people, making it difficult for them to meet friends and family. “The internal regime decapitalises socially, and I have met women who explained to me that they felt like robots”. This highlights the so-called Italia Syndrome, named after Romanian women who migrated to Italy to care for the elderly and who, upon returning home, needed a recovery process after isolation.

“We learned this with the pandemic, but they were already experiencing it before”, warns Poblet, who points out that the only alternative they have in order not to lose their jobs is to use technology and, secondly, to try to negotiate days off. “Many cannot give up work because that would mean not sending money to their families and, in addition, there is no collective bargaining agreement, and no labour inspections can be carried out because they are in private homes”. Negotiation, therefore, is between private individuals and, often, the expert explains, families believe that the discomfort of the person hired is due to migratory grief and not to the working conditions: “Working as an intern is to be permanently in someone else’s life”.

Other factors and groups at risk

Loneliness affects everyone, but especially targeted and stigmatised groups. This is the case, for example, with the LGTBIQ+ group, whose loneliness has been little analysed, and which only has specific data in the Netherlands. According to the article Solitude, ageing and sexual and gender diversity. La experiencia de la Fundació Enllaç [June 2022], by Josep Maria Mesquida, Joan Casas-Martí and Adela Boixadós, moderate loneliness among LGTBI people stands at 34% (12 points higher than the average for the entire population) and extreme loneliness stands at 16% (13 points higher).

Another group at risk is that of people with disabilities, 50.6% of whom claim to be in a situation of loneliness, according to the State Observatory on Unwanted Loneliness. A higher prevalence is also evident among people with mental health problems and mental illnesses that are not considered disabilities. Stigma and isolation keep these people away from many areas of socialisation, increasing their sense of loneliness and making it necessary for them to take part in initiatives such as the Espai de Lleure de l’Ateneu Social Club. This space is aimed at people with long-term mental health problems and offers guided workshops, self-managed activities, social exchanges, outings and cultural events.