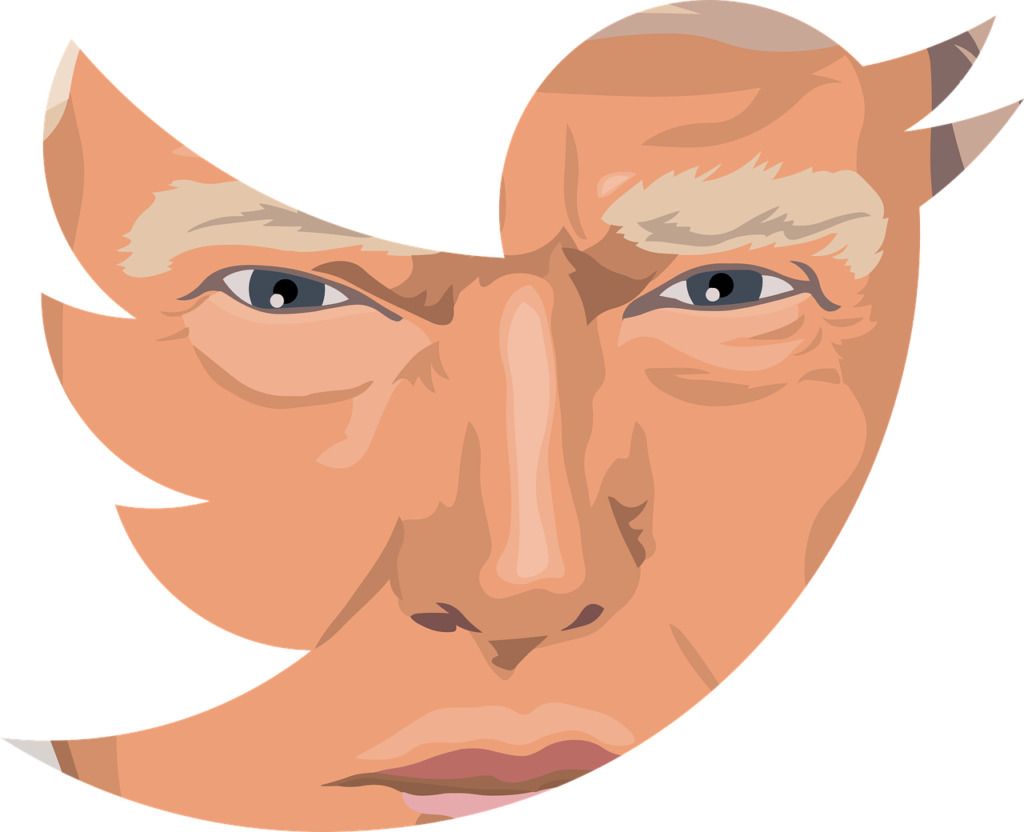

Under Trump, US politics is moving towards techno-feudalism. Silicon Valley is redefining power, with figures like Musk leading radical change. Neither neoliberal nor neoconservative, this new era marks a major political realignment.

In recent years, we have seen the political landscape in the United States shift towards a new paradigm that Yanis Varoufakis calls ‘techno-feudalism’. This term describes a dynamic in which large technology platforms act as new centres of power, disrupting traditional structures. With the Trump administration, these tech companies have found fertile ground to expand their influence and redefine the dynamics of political and economic power. The new administration will be neither strictly neoliberal nor neoconservative, but techno-feudal.

The new feudal lords

We already know that Elon Musk, the world’s richest man and Trump’s current right-hand man, will lead the new Office of Government Efficiency with businessman Vivek Ramaswamy, which will focus on federal spending and optimising government operations. But it’s not just him.

Mark Zuckerberg, in his recent interview on Joe Rogan’s podcast (arguably the most influential podcast out there right now), also reflects this shift, adapting to less interventionist policies on content control by arguing the need to protect free speech and for companies to adopt more ‘masculine energy’. Meta, Zuckerberg’s company, has softened its policy on moderating fake news, similar to what Elon Musk has implemented at Twitter.

And Peter Thiel, former CEO of Paypal, who in a recent article in the Financial Times entitled “A Time for Reconciliation’ called for a rethink of political alliances, driven by the power of Silicon Valley. ‘We are seeing the tech sector redefine the rules of the political game,’ Thiel notes in his article. These decisions, far from being purely technical, are evidence of a strategic approach to Trump’s policy approach.

These plans not only represent a radical restructuring of the state apparatus but can also be interpreted as a victory for the accelerationist thesis. This approach, which proposes to use the very dynamics of capitalism to reach a point of collapse or total transformation, is reflected in the strategy of the Department of Government Efficiency. By dismantling part of the traditional bureaucracy and encouraging deregulation, the key figures behind this project, such as Elon Musk and Vivek Ramaswamy, are implementing a model that seeks to accelerate technological and economic processes, even if this implies a weakening of traditional public structures. The dismantling of classical institutions is underpinned by the mantra that only technological progress will set us free. But the reality, at least the immediate reality, is quite different: the feudal lords are back.

Not strictly neoliberal either

The Trump administration’s move away from neoliberalism is particularly evident in its economic and trade policies. Unlike his predecessors, Trump has not defended the classic principles of free trade, but has adopted a protectionist stance, imposing tariffs on products from countries such as China. Stephen Miran, a member of Trump’s Council of Economic Advisers, has backed these measures, arguing that they protect national interests in the face of unchecked globalisation. Jan Hatzius, chief investment officer at Goldman Sachs, has also pointed out that Trump’s promises to reduce budget deficits have not been kept, which is also a departure from neoliberal ideals of fiscal discipline.

But if the statements of two figures clearly linked to the economic right seem suspicious, read what Nobel laureate Joseph Stigliz had to say in an interview in ELPAÍS, in which he explains why Trump breaks with the foundations of classical neoliberalism: “Trump, for example, is not exactly a neoliberal, but a nationalist who has built a coalition between those who feel disaffected and an important group of businessmen.

Not strictly neoconservative either

The Trump administration has also shown an ambivalent relationship with neoconservatism. Although relevant figures such as J.D. Vance, the future Vice President of the United States, represent classic moral conservative values (against abortion rights, gay marriage, etc.), Trump has made clear his disdain for neoconservatives. Specifically, Trump’s rejection is directed at those “hawks” who have been part of the administration and the intelligence community that have shaped the country’s military policy in recent decades. In an interview with Robert F. Kennedy Jr, the future head of the Department of Health and Human Services (and famous for his statements against the COVID vaccination), in a conversation with Jordan Peterson, he explicitly mentioned the strong rejection by Trump and his inner circle of those neo-conservatives associated with the arms industry and its interventionist international agenda.

This is not to say that Trump is a moral liberal, but rather that his stance on international policy is less imperialist and somewhat more isolationist than one might expect from the leader of the Republican Party. And therein lies the rub: this realignment of positions would not have been possible if the Democratic Party had not abandoned its base.

Democrats neglect their constituency

At the Democratic National Convention, which confirmed Kamala Harris as the party’s vice-presidential candidate, traditional neoconservative figures such as John Bolton, former head of the Department of Homeland Security during one year of Trump’s first term, and Dick Cheney, vice president under George Bush, expressed their support for the Democratic ticket. This underscores how internal shifts in the two parties have led to unexpected ideological movements and unusual alliances in an increasingly polarised political landscape.

Part of this shift in the Republican Party, led by Donald Trump, who recently described it as ‘the party of the working man’, is also due to the Democratic Party’s neglect of its traditional base. Over the past few decades, the Democrats have drifted away from the economic and social concerns of the working class, particularly in the industrial Blue Belt states that were historically the party’s strongholds. This shift has been compounded by the silencing of critical voices within the party itself, such as Bernie Sanders, who has been a consistent advocate of workers’ rights, economic redistribution and strengthening the welfare state.

Despite his popularity among the progressive grassroots and young voters, Sanders has faced an institutional boycott from the Democratic Party leadership, particularly during the 2016 and 2020 presidential primaries. This disregard for more radical proposals aligned with the needs of the working class has created a disconnect between the party and its historic constituency. Instead, the Democrats have prioritised alliances with the urban, cosmopolitan and corporate sectors, leaving a vacuum that the Republican Party, under Trump’s leadership, has been able to capitalise on.

In short, the Trump administration, together with key figures in the technology sector, has consolidated a new political cycle that transcends the traditional categories of neoconservative and neoliberal. This shift, driven in part by the emerging power of technology platforms and a strategic rejection of traditional interventionist politics, defines the new political era of techno-feudalism. In this context, not only is US politics being redefined, but so are the ways in which power is exercised in the 21st century.