Sònia Estradé is one of the 14% of women scientists working internationally in the field of neuroscience and nanotechnology, a highly masculinised speciality. Nowadays, the majority of university graduates in Spain who obtain the best qualifications are women, but the participation of women in research and teaching is far from equal to that of men and decreases notably in the highest professional echelons.

Estradé, as well as her scientific and technological colleagues, encounter two types of segregation on a daily basis. Horizontal segregation: the different women working in science are spread across different fields. And vertical segregation, the famous “glass ceiling”, where women do not occupy even 20% of positions, “not even adding the fields where there is a lot of feminisation, such as biomedicine”, says Estradé.

The Association of Women Researchers and Technologists (AMIT), of which Estradé is a member, aims to be “the voice and support network for all women researchers and university women who are aware of working together to achieve the full participation of women in research, science and technology”. In a highly masculinised world, sisterhood takes on great importance. AMIT works to give visibility to women scientists both in society and in the media.

“Society has prejudices that are also reflected in science”.

Isabel Muntané, coordinator of the Master’s Degree in Gender and Communication at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, states that “there has always been an invisibilisation of female knowledge”. For Muntané, the presence of women in opinion spaces is key: “to give an opinion is to create another imaginary, it generates reflection, and reflection provides citizens with tools”.

In this sense, Sònia Estradé considers that everything they do as women scientists returns to society through the press. “The proportion of women and men scientists is 40% – 60% respectively, regardless of the positions held by each one, 90% of the time men appear in the press”, denounces Estradé. He also analyses that when a report is made in which the researcher is a man, “the character is portrayed more as a leader, guru and his trajectory, while he is qualified”. On the other hand, if the report deals with a study carried out by a woman scientist, Estradé says, it focuses purely on describing the case.

Outreach work is very important to reverse this situation of inequality. AMIT calls on the media to see how and when they treat each scientific news item, but they also work with young people. “We try to reach young people, society in general, and we also work to change university policies”, explains Estradé, who points out that “at present, there are no gender research policies”. One of the Association’s initiatives in terms of dissemination among young people consists of a prize-giving ceremony for research work in the Baccalaureate, entitled Women in Science and Technology.

“Either the teachers will introduce you to the references, or you won’t have them”.

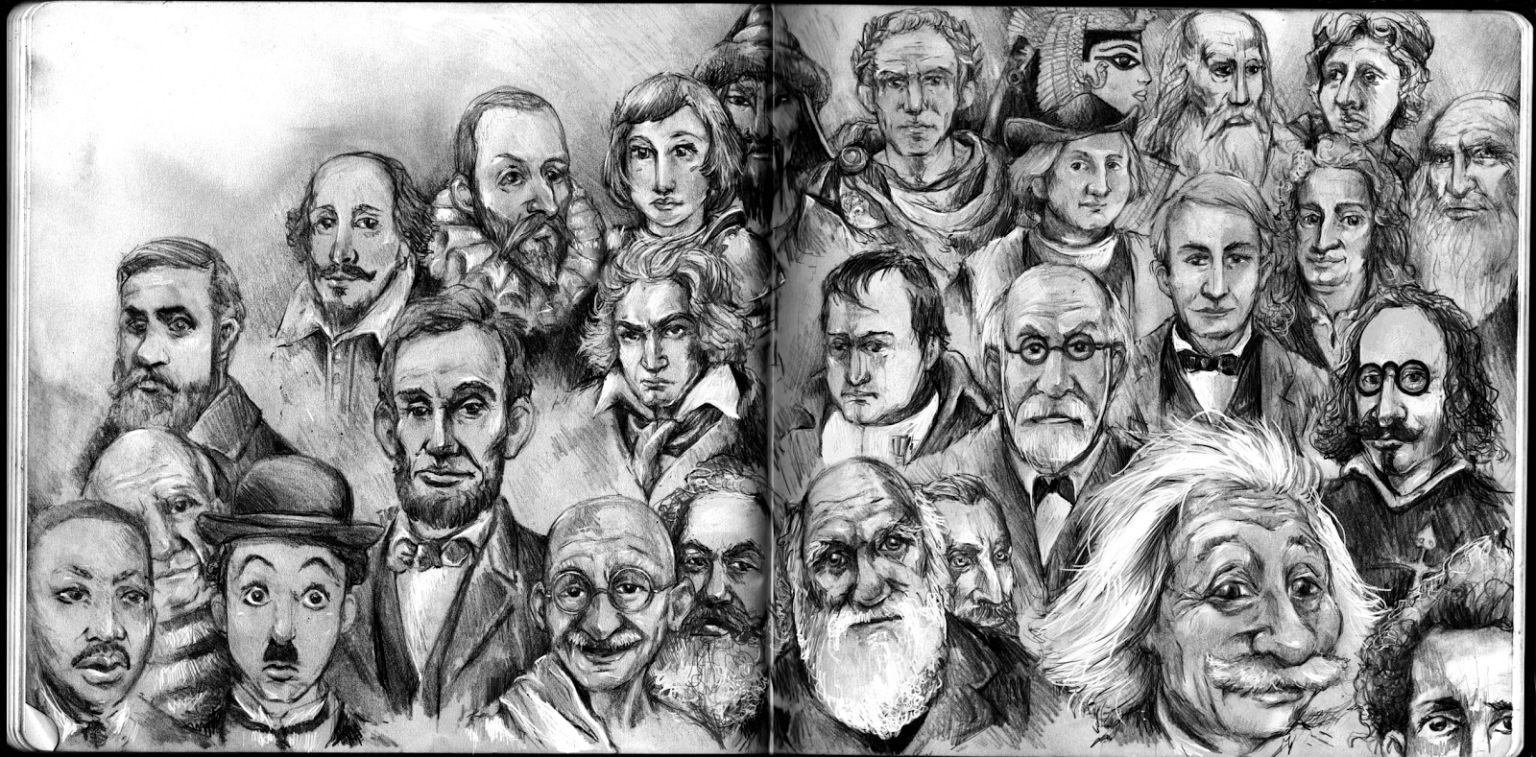

Isabel Muntané recalls that “we see this from childhood: women do not appear in textbooks and, for children, not having female references in any field means not existing”. Today, with the textbooks used in schools, the responsibility falls on the school curricula. “The teachers introduce them or the children won’t have them”, says Montaner.

The education co-operative Eduxarxa (Barcelona) also stresses the importance of role models, both at school and in the media: “when you ask children what they want to be when they grow up, they answer policeman or cook. Here we see the importance of the media and television, which, when they want to, can have a great deal of influence”, says Àngela García, a member of Eduxarxa.

This cooperative organised a visit by women scientists from the Barcelona particle accelerator to several secondary schools to raise awareness among students of the role of women in science. They carried out a questionnaire before and after the workshops to see how young people’s perception of women in science was evolving.

“We saw that girls like science a lot and young people in general do not tend to masculinise the figure of the scientist when asked explicitly, but, on the contrary, unconsciously there is a gender bias”. As an experiment, they gave the average grade of the subjects taken in a high school separated by gender, but without specifying it, and “although girls were always ahead, the class tended to say that boys were more successful. In technology, for example, no school considered that girls could have a higher average”.

The authors of the study wanted to find out whether they had been taught gender roles in their childhood through play or through the cartoons they watched. They found that “many girls had played football and many boys had played with dolls. There was no apparent role marking to justify these perceptions”. So they asked them directly and the answer surprised them: “they told us that, in society, on TV, in advertisements or series, there were not as many references of successful women in science as there were of men”.

Thus, Àngela García says that, although the answer given by the children hides a reality that they did not like, they were pleasantly surprised that the “kids were aware of the bias to which society exposes them”. This, according to Àngela García, is the basis for changing many things and, as proof, at the end of the workshops, one of the boys who was asked if his perception of women scientists had changed replied: “Yes, now I think that women can do everything”.